Editor’s note: we have an updated review for the newer edition of Chess-à-tête here.

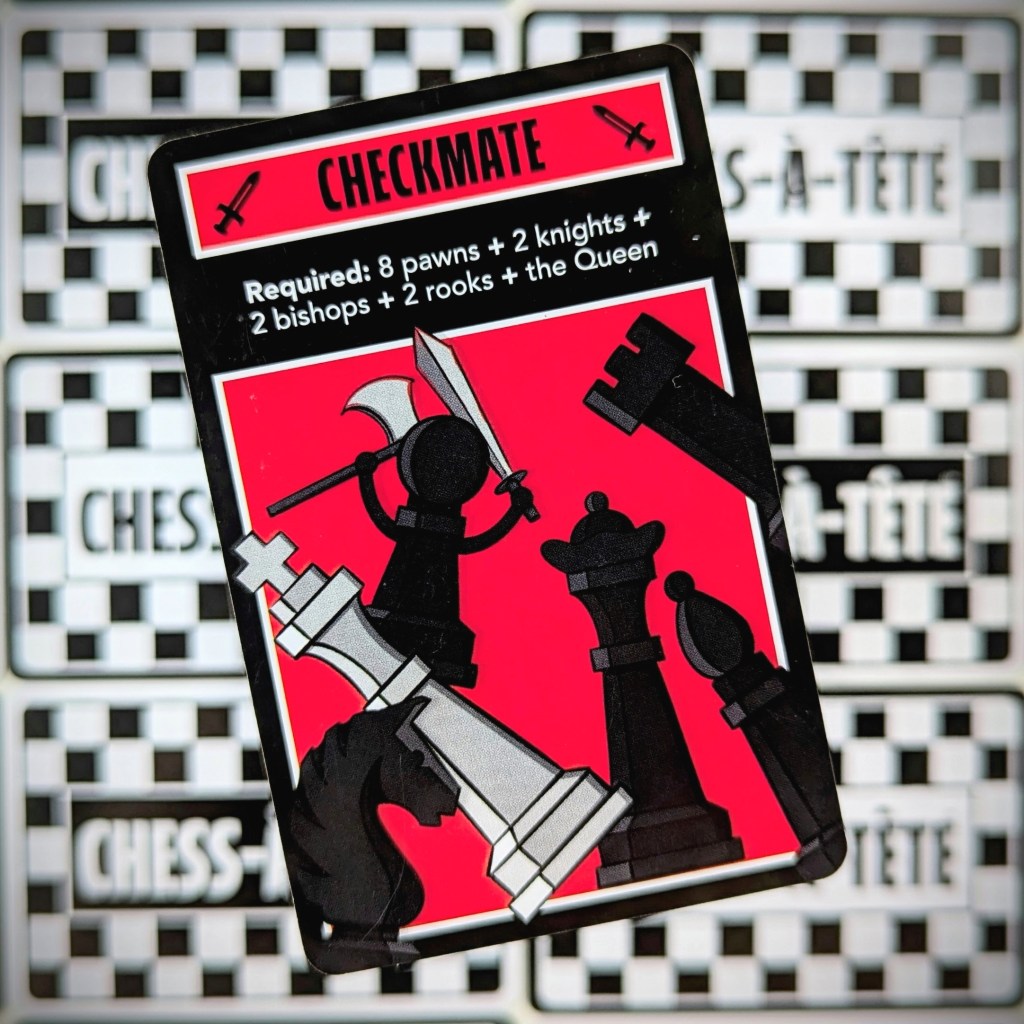

Chess-à-tête is a 2-player card game unsurprisingly themed around…chess! Players are opposing military factions racing to build their chess armies – can you survive long enough to destroy your opponent?

Game overview:

👥 2 players

⌛ 10-45 minutes

🧠 14 years and up

Each player starts with a deck of identical cards (one white, one black), a King card in play and 7 cards in their hand. On their turn, players can play up to 3 cards, which could be:

- More chess pieces. Each chess piece has its own health (hit points), and some pawns have additional abilities, e.g., the Medic Pawn has the instant ability to resurrect a playing piece from your ‘graveyard’ (discard pile).

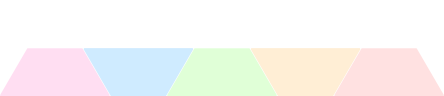

- Attack cards (used once per turn). Each card has an attack value and lists required chess pieces that you need to have in your army to launch that attack. These cards also function as defend cards.

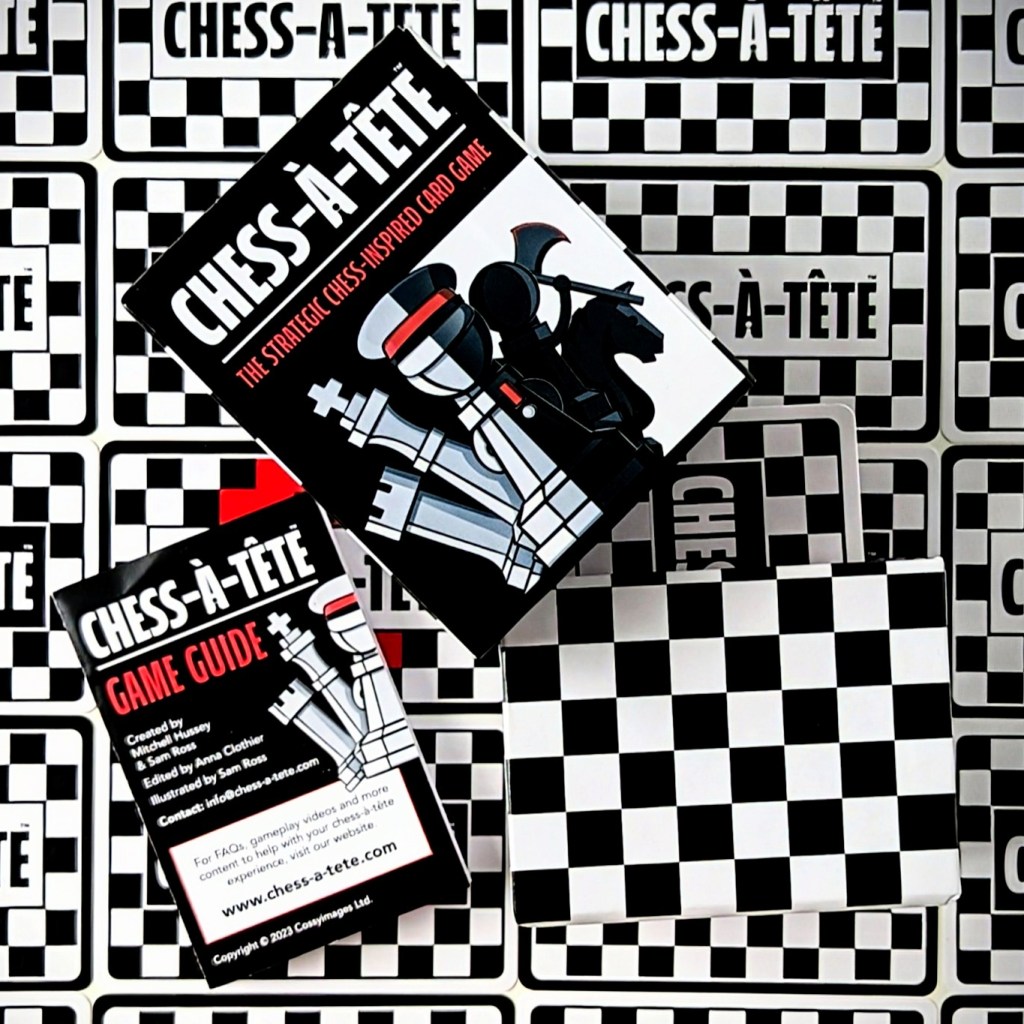

- Action cards. Action cards do a variety of things, from making your opponent discard cards, to stealing an opponent’s piece, to blocking an opponent’s card.

If a player chooses to play an attack card, then one of three things can happen:

- The opposing player can’t (or chooses not to) defend. The opposing player must then send pieces from their army to their graveyard with hit points that total the value on the attack card.

- The opposing player plays a defend card that has equal value to the attack. This is a ‘stalemate’ and all the chess pieces used in the attack and defence (from both players) get sent to their respective graveyards.

- The opposing player plays a defend card with a higher value than the attack card. The attacker loses the battle, and the chess pieces they used in the attack go to their graveyard. They also lose additional chess pieces from their army with hit points that total the value of the defend card.

There are three ways to end a game of Chess-à-tête. Take out your opponent’s King – you win! Get a full chess set and play Checkmate (action card) – you win! Run out of cards to draw – you lose!

What we think:

We have one big criticism with Chess-à-tête: the rulebook. As you start playing the game, it becomes clear that some details are missing, and some of the language isn’t clear or laid out in a logical way. For the first few games, we were constantly getting pulled out of the game with questions, checking the rules (or online FAQs) and not finding the answers, to the point that it became frustrating.

Here are just some examples:

- The term ‘army’ is used to refer to all the chess pieces you have in play, but it is also used to refer to the specific pieces you are using in an attack (e.g. the Army of the Dead action card says to “summon” an army of pieces and an attack card from your graveyard).

- It uses ‘on turn’ to refer to action cards when at least one of them (a card blocker) is not used on your turn.

- The rules don’t explain whether you need to round up or down when you lose an attack and don’t have pieces that match the exact attack value to discard (NOTE: the designer has clarified that you do round down).

- The rules don’t make it clear that there’s a limit to the chess pieces you can play (we realised this by accident when we came across an action card that increases the limit).

- What happens to the loser’s pieces after a battle is described under the wrong section of the rules (under Defending rather than Losing a battle); this could be missed if you are quick referencing specific sections during a game.

Once we got to grips with the rules (or picked house rules when we weren’t sure…), Chess-à-tête became a fun, quick take-that card game. The failsafe of the game ending when someone’s deck runs out means it doesn’t outstay its welcome. If games with direct aggressive conflict or ‘take that’ mechanics frustrate you (like me!), the short playtime makes it bearable here.

Once we got to grips with the rules (or picked house rules when we weren’t sure…), Chess-à-tête became a fun, quick take-that card game.

Sometimes a player has a hand of cards they struggle to use, but this is mitigated by a rule that a player can choose to discard and redraw a card instead of playing a card. We added a house rule that you can mulligan once at the start of the game (discard and redraw whole hand, shuffle discard back into the deck), which worked well when our starting hands were pretty much unusable, i.e. full of attack cards .

Strategy in Chess-à-tête is limited to optimising what you put in play or send to graveyard to make best use of actions/abilities. There can also be an element of running through your deck to find specific cards you think can win the game for you. The actions/abilities can be stacked to make some fun combos. My only concern is the long-term replayability: the more games we played the more it started to feel repetitive, staving off defeat whilst racing through the deck to get the same cards needed to win.

The theme is an interesting choice, when chess can be like marmite – Matt loves it, I hate it! The theming in Chess-à-tête is mainly limited to the card art and descriptions; e.g., the attack/defence cards are names after real chess moves (e.g. Fianchetto, Prophylaxis, and Gambit). It’s a nice touch for chess fans, but this is where the similarities end. The gameplay itself isn’t really chess-like at all. This puts Chess-à-tête in a strange position; people who don’t like chess will be put off by the theme, people who like chess may be keen but then disappointed when it doesn’t play like chess. This is a shame, because even though I wasn’t initially drawn to the game, I enjoyed it for what it is.

The theme is an interesting choice, when chess can be like marmite – Matt loves it, I hate it!

Chess-à-tête works well as a travel game (small box) and fits into that lovely subsection of card games that you’d take to the pub/coffee shop for as a quick filler. Its table footprint isn’t too big, and you can tweak the recommended layout to take up less space if needed.

What we like:

- Fun to play with some interesting actions/abilities (especially if you can stack them).

- Good travel option (light, fast playing, small table footprint).

- Clean, almost minimalist-style artwork.

What we don’t like:

- The rules (and some on-card language) are lacking or unclear in places.

- It starts to feel repetitive after a few games, questioning longetivity.

- The theme may put some people off trying it.

Final thoughts:

Despite the theme (in my case!), Chess-à-tête is a neat little game. It’s strategy-light and heavy on luck-of-the-draw, but there are some choices you can make (depending on how the cards come out!) that make for a fun playthrough. The main challenge is unpicking the rules, which I found particularly frustrating. I also felt there was a potential risk of the game getting a bit repetitive for me. It’s not one for our collection, but if you’re looking for a fun ‘filler’ game with a bit of conflict, I recommend trying Chess-à-tête for yourself.

If you’re intrigued by Chess-à-tête, you might be interested to know that the second edition of Chess-à-tête will be launching on Kickstarter soon. There are some changes between the first and second edition, notably updates to the art style and tweaks to the card designs. The designer has also confirmed that the rules will be improved in the second edition, which will hopefully address the issues we came across. For more information, check out Chess-à-tête on Instagram for updates.

This game was kindly loaned for review via the UK Board Game Review Circle. All opinions are ours and our reviews are always honest.